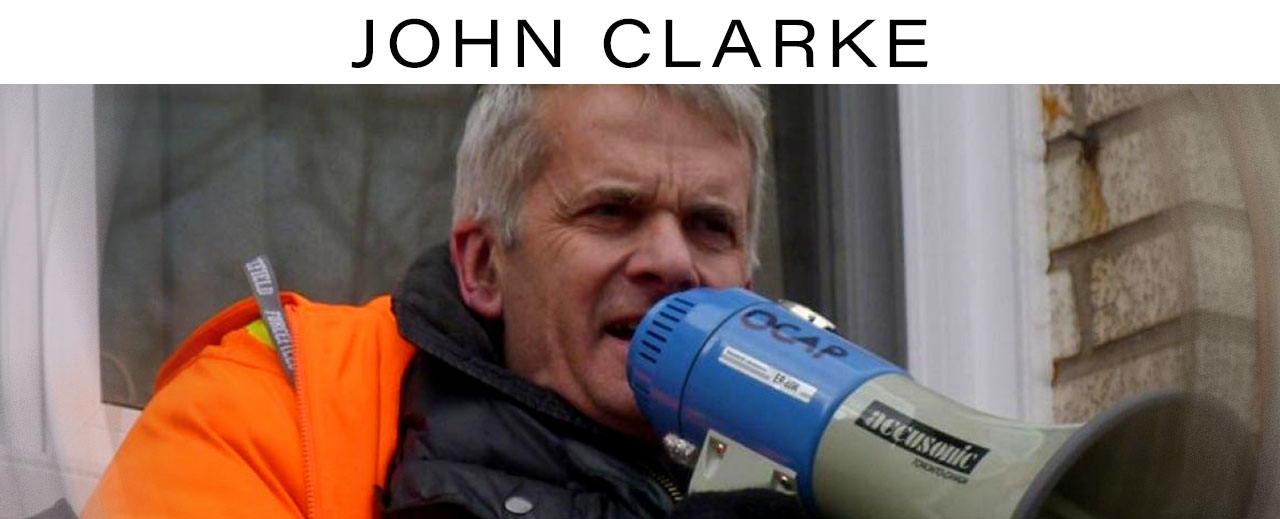

Written originally for Counterfire.

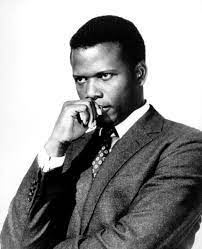

Sidney Poitier, who died on 7 January, at the age of 94, was ‘the only Black man to consistently win leading roles in major films from the late 1950s through the late 1960s.’ During those years, he ‘broke the mold of what a Black actor could be in Hollywood.’ This personal achievement, moreover, both reflected and influenced the broader struggle against racial oppression in the US. That ‘his screen life intertwined with that of the civil rights movement’ can be shown with one powerful example.

There is a scene in the great film In the Heat of Night, made in 1967, in which Poitier plays a Black northern detective, Virgil Tibbs, drawn into helping to solve a murder in a small southern town. He and the local police chief visit the estate of a plantation owner who is so outraged at being questioned by a Black man that he slaps Tibbs across the face. The backhander is immediately returned, to the shock and horror of everyone present.

It is impossible to overstate how startling it was at the time for a major movie to feature such an act of retaliation by a Black person and how inspiring it was to those facing racism and the institutionalised violence that upheld it. Before he agreed to take on the role, Poitier proposed that the retaliatory slap be included in the scene and he even amended his contract so that it couldn’t be cut from the scene before the movie was released.

In the Heat of the Night was met with hatred by those who opposed the civil rights struggle, even when it was still being produced. It was too dangerous to actually film it in the south but the scene involving the encounter with the racist plantation owner did require three days at a southern location. So tense was this undertaking that ‘pickup trucks full of drunk men circled the hotel where Poitier was staying’ and the actor slept with a gun under his pillow.

Life and career

Poitier’s parents were tomato farmers in the Bahamas and he was born during a family visit to Florida, in 1927. When he was 15, his parents sent him back to Miami in the hopes that life there would have more opportunities for him. He soon moved up to New York and tried to become an actor but had little success at first, working as a dishwasher. He managed to find a place with the American Negro Theatre and an understudy role meant opportunities on Broadway. This, in turn, led to his first film role in the 1950s, in No Way Out, in which he played a Black doctor who had to treat a racist patient.

Poitier was given increasingly major roles and, in 1958, became the first Black person to be nominated for an Oscar, for his part in The Defiant Ones. His success continued on both stage and screen until the landmark year of 1967, in which he starred in To Sir, With Love, In the Heat of the Night and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner. During this period, he simultaneously gave support to the civil rights movement, encouraged to do so by his friend, Harry Belafonte.

As the 1970s unfolded, Poitier turned to directing movies, his greatest success coming in 1980 with Stir Crazy. Though his most successful acting roles were behind him, he continued to appear in movies well into the 1990s, with his final role in The Jackal, in 1997.

In 1967, at the 10th anniversary convention banquet of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Martin Luther King Jr. introduced Poitier as the event’s keynote speaker. The actor had played an important role in challenging racism in the US and the leaders of the civil rights movement were anxious to honour that role. Still, there have also been more critical voices raised about the characters he brought to life on screen. It has been pointed out that they always ‘radiated goodness’ and stayed within boundaries that were acceptable to white liberals. In the 1958 film, The Defiant Ones, Poitier played an escaped prisoner handcuffed to a racist. The ending has him jump off a train to stick with his new found friend. James Baldwin tellingly reported seeing the film in Harlem, where members of a Black audience called out, “Get back on the train, you fool!”

Even at the time of his greatest success, in 1967, critics suggested that ‘Poitier's saintly, non-sexualized characters bore little resemblance to the complex realities of African-American life.’ Black playwright Clifford Mason, in a New York Times column, bitingly asserted that he always played the role of ‘a good guy in a totally white world, with no wife, no sweetheart, no woman to love or kiss, helping the white man solve the white man's problem.’

No doubt, by the late 60s, the struggle of Black people in the US had to go beyond liberalism and respectability and move in directions Poitier wouldn’t go or Hollywood accept. Yet the son of a poor farming family in the Bahamas, who won renown while refusing to accept the degrading roles set aside for Black actors, deserves to be remembered. The man who demanded that the film character he was playing would deliver a retaliatory slap to the face of the racist plantation owner should be honoured. Though more radical voices needed to be raised, Sidney Poitier’s message will still be a lasting one.