In the space of a few weeks, the course of history has been radically altered. The pandemic has tipped the already faltering global economy over the edge and an economic slump, without precedent since the Great Depression, is unfolding. This situation is so drastic that we might not wish to consider that the biomedical and economic crises are occurring in the shadow of an ecological disaster with even more appalling implications. However, millions of people in India and Bangladesh, facing the Super Cyclone Amphan, have no choice but to deal with the pandemic and the impact of climate change at the same time.

The Canadian economy lost almost two million jobs in April and it is becoming clear that things are not going to spring back after the present lockdown comes to an end. It is suggested that, in the US, some ‘42% of recent layoffs will result in permanent job loss.’ The initial hopes for a V shaped recovery have faded and expressions of optimism ‘are beginning to dwindle to just the leaders of governments and finance.’ It seems highly unlikely that the initial lockdowns will limit the spread of the coronavirus enough to avoid having to repeat them. News from several countries, including and especially China, strongly suggests otherwise and further measures of isolation will, of course, entail even more economic dislocation. However, even if COVID-19 were to mutate itself into a state of harmlessness tomorrow, we would still face the prospect of a protracted period of mass unemployment. Furthermore, as this unfolds, governments will be anxious to impose the bill for the massive costs of responding to the pandemic and an austerity driven attack on public services is to be expected.

When a neoliberal strategy was taken up by the drivers of global capitalism in the 1970s, they were moving to reverse a period of relative class compromise that had existed in the years since the Second World War. This period, at least in the West, had been marked by very significant concessions to working class populations. Workers’ wages were increased as were levels of social provision. This period has sometimes been referred to as the ‘post war settlement’ and it most certainly was marked by unspoken compromises on both sides. Poverty was not eliminated but income support, social housing and public healthcare provided real improvements. Trade unions made major advances and employers and the state tolerated this. In return, however, union leaderships accepted very definite limits on the forms of activity they would engage in. A compartmentalized and restricted class struggle ensured that the concessions that were granted bought, in return, an effective pledge to avoid sweeping and generalized social resistance and, most assuredly, an acceptance of the capitalist system itself.

Governments enacted measures of reform that improved things for working class populations during this period. Sometimes, the reforms were granted by parties of Big Business and, very often, by social democrats in power. The latter had by this time set aside any effective commitment to social transformation and were ‘reformist’ in the most literal sense.

It would be totally inaccurate and unjust to suggest that the neoliberal period has advanced without very major resistance but it has still been overwhelmingly successful in obtaining its objective of increasing the levels of exploitation and weakening the capacity of the working class to offer opposition. Certainly, there have been times when very sharp confrontations have occurred but it is striking that, up until this time, the mechanisms of class compromise have remained largely intact. Social democratic parties have carried on as mainstream political forces but they have bee transformed, for the most part, into political formations that accept a place within a neoliberal austerity consensus and their past role as agents of limited change has given over to one of reformism without reforms. The trade unions, dominated by a bureaucratic layer that has expanded and tightened its grip considerably, have continued to operate within the confines of a system of compromise that the other side no longer adheres to. Working class gains have been reversed, defeats have been imposed and concessions have been brokered as the unions continue to accept a system of state imposed ‘labour relations’ that massively limit workers’ power, even though the benefits of working within such confines have long since dried up.

Forms of Struggle

In the period we have now entered, there are going to have to be some very real changes in how we fight and how we organize in the face of attack. The forms of limited social resistance that were created for a period of relative compromise failed badly during the years of neoliberal attack but they would be catastrophically deficient in the situation we now face. I’d like to suggest a few considerations in this regard.

Firstly, the trade union as a bureaucratically controlled formation, with most of its members demobilized most of the time, is not a viable structure for the coming period. There is going to be a massive loss of jobs and a huge contraction of the ‘dues base.’ With vicious attacks on public services in the wings, both private and public sector unions are going to impacted severely. Moreover, employers will go on the offensive to an unprecedented degree and any possibility of mounting a defence that is focused on protecting individual collective agreements will be precluded. There is going to have to be a generalized united resistance that unites workers with communities under attack. This will have to reach the level of a mass movement and that will not be possible without rejuvenated rank and file controlled unions. The task of transformation will be formidable but it will be greatly assisted by the sheer impossibility of continuing with the old rituals of token resistance.

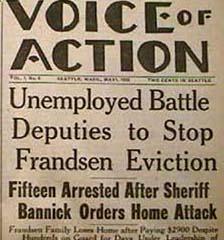

Secondly, the mass mobilization of the unemployed, on a scale surpassing the movements of the 1930s, is a strategic imperative. The fallout of the Wall Street Crash, in 1929, took several years to play out. The economic devastation unleashed by the pandemic will strike far more rapidly. We are going to be looking at masses of people with very little or no income, a huge rise in homelessness, a crisis of hunger and a wave of economic evictions and we will have to develop a capacity to take action on these fronts. This will have to happen on a huge scale and in militant and effective forms. The unemployed movements of the 1930s were strongly anti-capitalist and very militant but they were also hampered by the perspective of the Third Period. We need to embrace the first two qualities but to put aside all sectarianism and work for maximum working class unity in the face of attack.

Thirdly, we will need to look for forms of democratic and dynamic organization to unite our struggles. This will be a period when we will have to forge a spirit of solidarity for survival and an ability to set it in motion. Some of the struggles we face will be extended but many of them will be short and sharp. A hospital or library may be threatened with closure, a particular social benefits office may need to be confronted, a family facing eviction may need supporters to prevent it or racist attacks by cops or fascists may need to be countered. Locally based forms of popular assemblies that can build the capacity of communities to defend themselves, while forging networks with other communities, can play a vital role in building mass resistance.

Fourthly, the role of anti-capitalist politics at a time like this is potentially decisive. The crisis that is unfolding is an expression of the utter failure of a system of such irrational destructiveness that it must be replaced. We are living at a time when the thinking of masses of people can undergo explosive changes but the forces capable of intervening are still very small. I once read an account, that I haven’t been able to relocate, of unemployed organizing in Michigan during the 1930s. A liberal commentator described a rally at which a communist speaker addressed a crowd of local tenants. The writer described being embarrassed for the speaker because he assumed the extreme and radical message would seem ridiculous to the crowd. Then, he turned and saw the men and women who had gathered, ‘their faces pinched by hunger’ savagely nodding their agreement. Of course, to the liberal observer, the message seemed outlandish but, to the working class people whose lives had been devastated, it seemed both reasonable and vital. The period we have entered is one in which we can get the same kind of collective nod to a message of anti-capitalism which means that we should debate our differences but unite in action and around fighting demands as a matter of urgency.

These few suggested considerations may deserve some criticism and, without doubt, can be added to. The main point, however, is that we are only beginning to appreciate the vast changes that have been unleashed by the pandemic and the broader crisis it is part of. The question of political intervention is decisive and the need to act immediate and pressing.