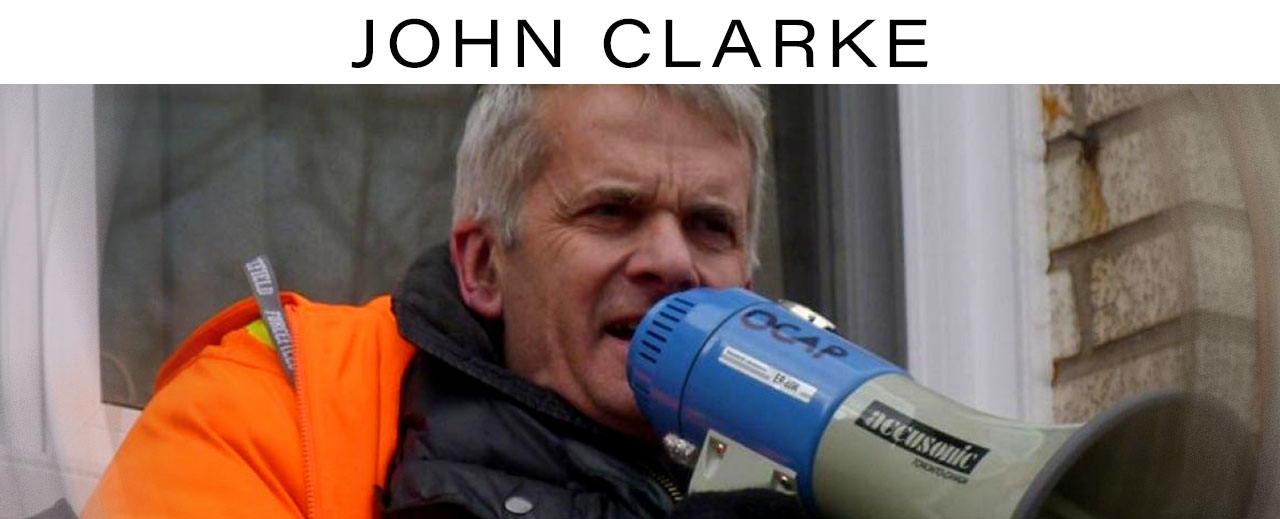

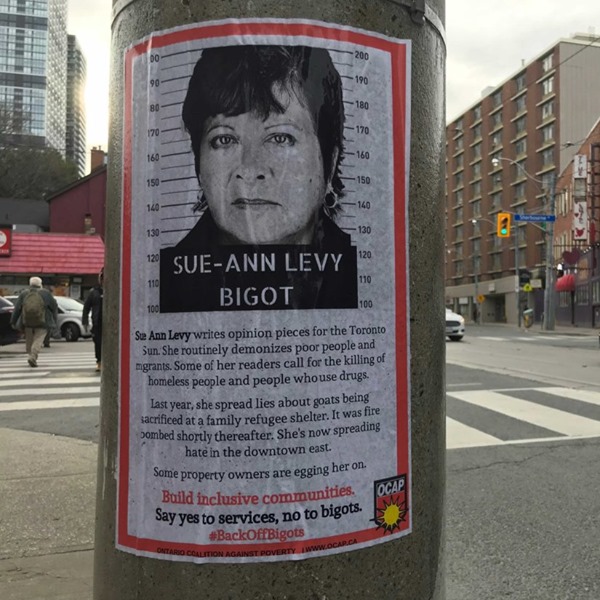

Toronto’s Downtown East is a neighbourhood that experiences very high levels of poverty and homelessness. It has long been contested territory, with the accelerating process of gentrification pitting upscale residents and businesses against the poor. This redevelopment has involved organized efforts to exclude and drive out services for homeless people. Recently, the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP), of which I am a long standing member, challenged Toronto Sun columnist, Sue-Ann Levy, an ideological attack dog whose writings support the gentrification process, demonize homeless people and promote efforts of to force out support services they rely on.

After OCAP put up posters in the area labelling Levy a ‘bigot,’ we received a cease and desist letter from the Sun’s lawyers, suggesting we had defamed her and even put her at some risk. OCAP will not be retracting its fair comment on the Sun’s attacks and we shall continue to take action in defence of homeless people in the area. What I want to take a look at here, however, is not the present conflict with the shock troops of gentrification and their inky enablers at the rightward limits of mainstream journalism. Rather, I want to consider the historical and present day context out of which hostility towards the homeless has been forged. The upscale residents we confront are focused on their property values and ‘quality of life’ and see the homeless as a threat to these things. Those who think like Levy, regard destitution as a product of moral failings. Their ideas and assumptions, however, are based on deeply ingrained societal attitudes that I want to explore.

MORAL POLICING

The poor and homeless have long been subjected to reluctant systems of social provision that are calculatedly inadequate and punitive. The notion that those who experience poverty and destitution are the architects of their own misery, in need of harsh corrective measures, is historically rooted and firmly entrenched. This goes back to the Elizabethan Poor Laws and has been incorporated into modern welfare systems. The homeless are, in many ways, considered the least ‘deserving’ segment of those in poverty. Their supposed moral failings and personal shortcomings are seen as having prevented them from even maintaining themselves in a state of housed poverty. Not surprisingly then, a particularly severe sense of social disapproval is reserved for the homeless. If they sleep on the streets, it is deemed to be a choice that their moral degeneracy has led them to make. If they turn to homeless shelters, they can expect the conditions of these facilities to be shockingly inadequate and rule bound. As they move around in the communities they are part of, the weight of moral judgement and societal hostility is ever present. This can take the form of intrusive social agency staff, disdainful members of the public, business owners who want them gone, police harassment that often goes over to brutality and even a rather bizarre newspaper columnist who follows them around with a view to recording their perceived moral failings.

In the context of an escalating political agenda of austerity and, with the process of urban redevelopment generating an ever worsening housing crisis, it is not surprising that the climate of hatred that homeless people face is getting worse. The developers and speculators have turned housing into a commodity that is simply unaffordable for many. The elimination of social housing and an array of social cutbacks, have dumped more people into the shelters and onto the streets. Politicians who facilitate this agenda increasingly look for ways to drive the problem from sight and callous and hostile attitudes to the homeless justify and facilitate such a response. A 2016 study of 187 US cities, conducted by the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty (NLCHP), found that ‘47% had laws prohibiting sitting and lying down in public, 32% outlawed loitering citywide and 6% restricted food sharing.’ A range of repressive measures have been used in the UK against homeless people, including pressing into service the 1824 Vagrancy Act. Under the regime of the infamous Viktor Orban, Hungary has gone so far as to actually declare the act of being homeless a criminal offence.

In Canada, the same kind of climate of hostility and readiness to displace homeless people has been very much in evidence. Attempts, over recent years, by homeless people in BC to survive by establishing tent cities have been responded to harshly by those in power. The clearing out of homeless encampments in Toronto has been an ongoing process. Under both Tory and Liberal governments in Ontario, the ironically misnamed Safe Streets Act has been used to persecute and criminalize homeless people driven to ask for spare change.

WORSENING ATTACKS

With the homeless crisis spinning out of control, short of major victories in the struggle for housing, there is no reason to believe that these attacks on the destitute victims of this crisis are going to ease up. The climate of hostility is, indeed, now producing ongoing physical attacks on homeless people. Advocates in Los Angeles have noted that expressions of hatred against the homeless and violent attacks on them are focused in areas of the city where gentrification is underway and upscale residents and business interests are working to drive them out.

Various other socially ingrained forms of bigotry interconnect with hostility towards the homeless and intensify the climate of hatred. As a settler state, Canada’s colonial oppression of Indigenous people has ensured that they experience homelessness to a massively disproportionate degree and those who do are especially vulnerable to anti-Indigenous racism. For reasons that are quite obvious, societal issues of misogyny and violence against women play out in the lives of those who are homeless with an intensified brutality. The same can most certainly be said of those who face homophobia and transphobia. The opioid crisis, moreover, provides an exceptional field of operations for the most extreme forms of moral judgement against homeless people. Drug users who are homeless and turn to safe injection facilities are targeted ruthlessly. Indeed, Ms. Levy’s admiring readers have commented on the Sun website on this very theme, including one noble soul who views the opioid crisis as an opportunity to ‘cull the bums and drug addicts,’ while suggesting that ‘it’s time to start thinning the herd.’

As a decade of low wage recovery gives over to conditions of global slump, the rise in homelessness that ensues will overwhelm stretched social services and shelter facilities. The visibility of the problem will increase dramatically and the war on homeless people will intensify. The situation facing the homeless, however, will only be a particularly sharp expression of the an attack faced by all working class people. The need, then, will be for a social movement against austerity that fights for housing and sees challenging homelessness as a vital part of a broader struggle.

Dealing with homeless deaths in Britain and Ireland in 2017, Keven Ovenden drew on an article Rosa Luxemburg wrote concerning a comparable tragedy that occurred in Berlin in 1912. Scores of homeless people died when they were fed cheap and contaminated food by those running a hostel. Luxemburg responded to those in the official workers’ movement who saw the terrible incident as a matter for social commentary, rather than political action. Those who died in the hostel were, for her, part of the working class and the inhuman conditions they faced should have been challenged as part of the broader struggle against capitalist exploitation.

If we are to address the homeless crisis and answer those who see homeless people as nothing more than pests to be driven from sight, then the struggle for housing for all must become a key objective for a united working class common front that challenges the agenda of austerity and social abandonment that stands in our way. If we do that, the grubby little prejudices of people like Sue-Ann Levy will simply be pushed aside by a united movement that reserves its anger for those who create homelessness and that acts in solidarity with those who have been thrown onto the streets.